It’s revolutionary: art sourced from a sustainable palette, a collection of materials that poses absolutely no potential harm to the viewer. Okay, maybe it’s not that revolutionary, but it’s a surprisingly difficult undertaking to accomplish. Between the manufacturing line and the ingredients used therein, it’s nearly impossible to find material that makes little to no impact on the environment and poses no toxic threat to those who spend time around it. That’s why, when installation artist Del Hardin Hoyle heard about Healthy Materials Lab’s work with the Rose Project—an affordable sustainable housing development in Minneapolis, Minn.—he was inspired. From seven unique materials chosen to create a safe and inviting interior space at The Rose, Hardin Hoyle created a series of sculptures to be placed on display in the Donghia healthier Materials Library at Parsons School of Design in New York City.

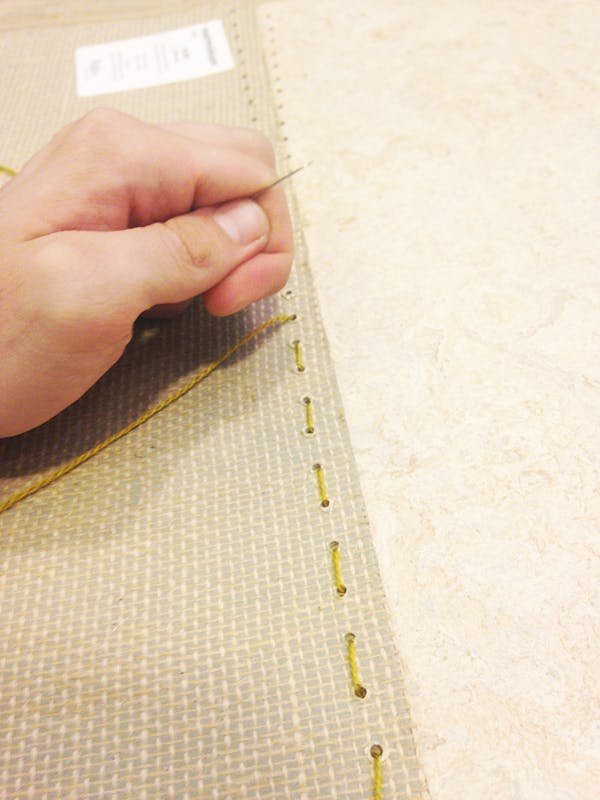

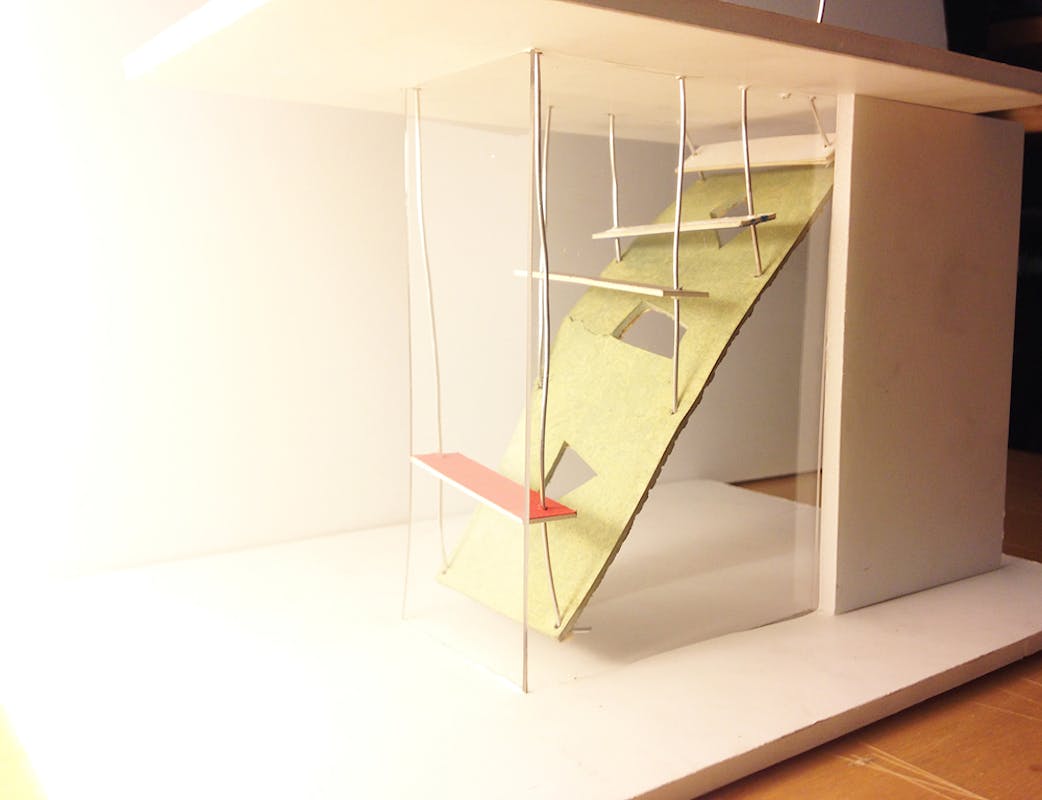

Original artwork & installation pieces by Del Hardin Hoyl. Photos courtesy of Del Hardin Hoyl.

These sculptures will be unveiled at the #Final7 event on Monday, Sept. 28, at the Donghia healthier Materials Library. To RSVP for the event click here.

Recently, Healthy Materials team member Marcea Decker sat down with Del Hardin Hoyle (www.delhardinhoyle.com) to find out a little more about the installation.

Marcea Decker (MD): Let’s start off by talking a little bit about yourself and your background, and how that lead you to collaborate with Healthy Materials Lab and the Donghia healthier Materials Library.

Del Hardin Hoyle (DHH): Well back in England, I was working with artists. I founded an art collective called It’s All Tropical, where we were working with artists and curating shows, as well as putting work in shows. So I started to collaborate with a lot of different people with different backgrounds, artists, furnishing designers, all these different skilled people. At the same time, my own practice was getting redefined through working as a technician in Sheffield University. I was teaching how to make furniture, workshop skills, so I was kind of broadening my palette of making. But my practice in general was fed through reusing or reappropriating materials, found objects, repurposed through sculpture and furniture design, gallery-based projects. So I got an awareness of—

I was trying to be a conscious artist with the things I was using.

Everything I have made in the last two years has all been made from scrap material that the University that I worked at were throwing out. Then coming here to study at The New School, and finding out about the Healthy Materials Lab, it seemed like the next step of doing—to meet with my trajectory as it is now, to refine it further through more knowledge of new technologies and materials, and the healthier side of materials in order to become a more conscious maker.

Original artwork & installation pieces by Del Hardin Hoyl. Photos courtesy of Del Hardin Hoyl.

MD: And so now you’re in the MFA Interior Design Program within the School of Constructed Environments at Parsons The New School For Design?

DHH: Yes, because I am always interested in how people respond to their surroundings. So by curating shows, it’s a great way to experiment in the process of spatial division, color, lighting, material qualities, and things like that, and see how people would react to it. So, using something that I found that was really ugly, and you know, dirty, next to something that’s really clean, or something in the dark, etc. All the kind of polar opposites of that. To get it back into the Healthy Materials Lab, it was the combination of wanting to become a more conscious maker and being aware of the content of the materials that I was using as an artist, but also the politics of the project as well sit really well—are really aligned with my own outlook. With the Rose [Apartments] in Minneapolis being about affordable housing, giving people who wouldn’t necessarily be able to afford to live in a place that has these more environmentally friendly materials in them, sits with my background. I’m from a very working class family, quite socialist, so this idea of everything for all, a better living standard for people who have not necessarily been able to afford that, really resonated with my own upbringing and my own standpoint now of how things should be.

MD: Do you find that the paradigm is shifting in Interiors, in terms of the dialog and study of healthy materials?

DHH: It feels like this shift that is happening in real time—I think there’s a definite shift. In the last 5 years or more, the environment has been a very hot topic in politics, or in the news, in the media. I think it’s finally sort of permeating through the industries that are feeding it. It does feel like the Healthy Materials Lab is at the forefront of this paradigm shift as you say, so we’re trying to highlight one, the good work that other projects are doing with healthier materials, but also trying to make people more aware of it. When I speak to people about what I’ve been doing, a lot of people don’t understand the thing of interior pollution, the off-gassing from things. Especially in a time now where everything is so readily available, and so disposable. It’s almost like the general thought process is, ‘it doesn’t matter.’ But when you start delving into the research, it’s terrifying. And it is something that needs to be shared and understood and tackled, and I think definitely the lab is making big steps to do that. From what I’ve seen, before a lot of other people are, which is great and exciting to be a part of that.

It does make me feel less self-conscious making sculptures out of this kind of stuff, it’s a nice feeling, it feels wholesome and worthwhile.

It’s something that is beneficial and the level that we’re doing it in the school, especially through the collaboration with the Donghia Healthier Materials Library, it’s a way of informing a generation that are going to come up through the industry and going to start leading that industry. So I think it’s really important, the point in which we are starting from is to try and encourage people who are in education, because that’s where you need to start, really. But then, also, that opens up the whole spectrum of informing an industry of what they use, and how that affects day to day life.

Original artwork & installation pieces by Del Hardin Hoyl. Photos courtesy of Del Hardin Hoyl.

MD: In terms of the installation you’ve created for the Donghia Healthier Materials Library, do you think that people would be surprised to find that many of the materials you used came from a healthier source? Is there a disconnect between knowing what’s really healthy and what isn’t?

DHH: Yeah, because that’s what’s the beauty of the materials and the danger at the same time—it’s so everyday. You see plywood all the time. People are used to seeing materials like carpet. That feels like why that awareness isn’t as apparent as it should be. So that disconnection with the sculptures that I’ve made, I think people would be surprised that they are used with healthier materials- I’ve tried to make something that is abstract but shows a trajectory of aspiration so that everything is moving up, or is on some sort of ascent, to try and instill the piece with some sort of trajectory of what the lab is trying to do, and in the process of doing, which is to grow, get larger, inform more people, and change the industry. I’ve tried to encompass that in an abstract way within the work that I’ve made.

MD: Are your installations up only for the opening, or will there be a continuous display of installations at the library?

DHH: It’s a continuous thing, for a month maybe in total. I am employed in the library, so my plan is to keep it moving, an accumulative project. So as time goes on, the installations will change and shift as new materials become available. Because there are always new breakthroughs and new materials that are healthy— or now they are not. Or this part of it is, but then you find out the process is constantly shifting, and

DHH: Yeah, because that’s what’s the beauty of the materials and the danger at the same time—it’s so everyday. You see plywood all the time. People are used to seeing materials like carpet. That feels like why that awareness isn’t as apparent as it should be. So that disconnection with the sculptures that I’ve made, I think people would be surprised that they are used with healthier materials- I’ve tried to make something that is abstract but shows a trajectory of aspiration so that everything is moving up, or is on some sort of ascent, to try and instill the piece with some sort of trajectory of what the lab is trying to do, and in the process of doing, which is to grow, get larger, inform more people, and change the industry. I’ve tried to encompass that in an abstract way within the work that I’ve made.

MD: Are your installations up only for the opening, or will there be a continuous display of installations at the library?

DHH: It’s a continuous thing, for a month maybe in total. I am employed in the library, so my plan is to keep it moving, an accumulative project. So as time goes on, the installations will change and shift as new materials become available. Because there are always new breakthroughs and new materials that are healthy— or now they are not. Or this part of it is, but then you find out the process is constantly shifting, and

I want to keep that fluidity in the installation pieces so that it is moving along at the same rate in which the lab is moving.

MD: It’s a really interesting way to put it, that not only is the library a resource, but so are the installations in terms of showcase what materials are available.

DHH: Yeah, and I’ve tried to use techniques within it to show ways of manipulating the materials. So, the plywood—I’ve made it so that there are no straight cuts, and there is no real link to the building industry, which is more on the design-side, there’s no measured right angles. It’s a very amoebic form, it’s got a fluidity to it. I try and make it pleasing to the eye and aesthetically attractive so that, as you were saying earlier, people who don’t necessary know it’s a healthy material may hopefully be drawn into the appeal of the aesthetics of it, and upon further investigation of it say “I didn’t know plywood has all of this horrible stuff in it”, but yet, this one hasn’t. And you can do all of this great interesting work with it. So that’s one idea. And the other thing within the sculpture is that things are all propping up against each other and leaning on each other, trying to show how in a domestic case, the materials are supporting one another in their utility in order to create the space. So I tried to get that in there through just creating relationships through contact. So little slots cutting through to fit, bits of stone raises up the carpet in a certain way, just to show: although there is a hierarchy, there is also a relationship between them to create the domestic interior.

Original artwork & installation pieces by Del Hardin Hoyl. Photos courtesy of Del Hardin Hoyl.

MD: I think it’s really cool to do it in that way, to bridge other disciplines. To have artists look at it and say- ‘oh what materials am I using’?

DHH: Yeah, which is like, when I first spoke to Jonsara Ruth with interest about the Healthy Materials Lab, we were going through my portfolio and looking at things. And first it was like ‘Oh this is nice… this is an interesting piece, but wait a minute, this paint you used is full of some horrible chemical, or this OSB board that you’ve used…’, which again everything I’ve used within the last two years I have pulled out of skips and trash from a school similar to Parsons. It was just like, wait a minute. I was trying to make good out of someone else’s bad action. So it made me feel really conscious— ok, there’s a whole world to explore. I think artists should be aware of that, because on a conceptual side of things, if an artist is supposed to be like someone within the world reflecting back into it with their creations, they should be aware of the environmental impact of what they’re doing. I think that’s why I moved into furniture design, because it felt more useful.

MD: Any final thoughts of what you hope the impact of this exhibit will achieve, or hoping that it will become a continuing thing?

DHH: I am hoping this is the beginning of a longstanding relationship, one where in a personal sense I can experiment and explore materials and get more understanding of the whole healthy materials movement, if you will. Which I’d like to feed into this exhibition as an ongoing cumulative process that is moving in real-time with findings as they happen. I can’t really speak more highly of this, it’s really interesting, it’s a really people-oriented thing.

I hope this exhibition breaks that translation of the thick scientific language, and works as a conduit between the audience that needs to know about what’s going on.

Read More

Join Our Academic Network

Get Access to our carefully researched and curated academic resources, including model syllabi and webinars. An email from an academic institution or a .edu email address is required. If your academic institution does not use .edu email addresses but you would like to join the network, please contact healthymaterialslab@newschool.edu.

Already have an account? Log in